In February I suggested that the SARS-CoV-2 virus and the COVID-19 disease it causes may be the black swan that push the global economy into recession. I suggested that uncertainty would be worse than definite bad news and that the second order impact of the virus on the economy due to individual, investor and corporate risk aversion would dwarf the first order impact. Unfortunately, this post has proven to be prescient and the economy is headed for recession.

Every day brings news of quarantines or companies like Volkswagen shutting down production. While some professions can work from home, and the trend towards remote work and flexible work will be accelerated, most are not in this privileged position, and the economic costs in terms of lost wages and production are enormous. On top of that everyone is becoming risk averse: companies are trimming costs and delaying investments. Individuals are delaying making big purchases of cars or houses and are changing their behavior to decrease exposure: not going out, traveling or going to work. Individually this makes sense, but collectively can lead to a huge decrease in corporate and consumer demand which will worsen the economic impact.

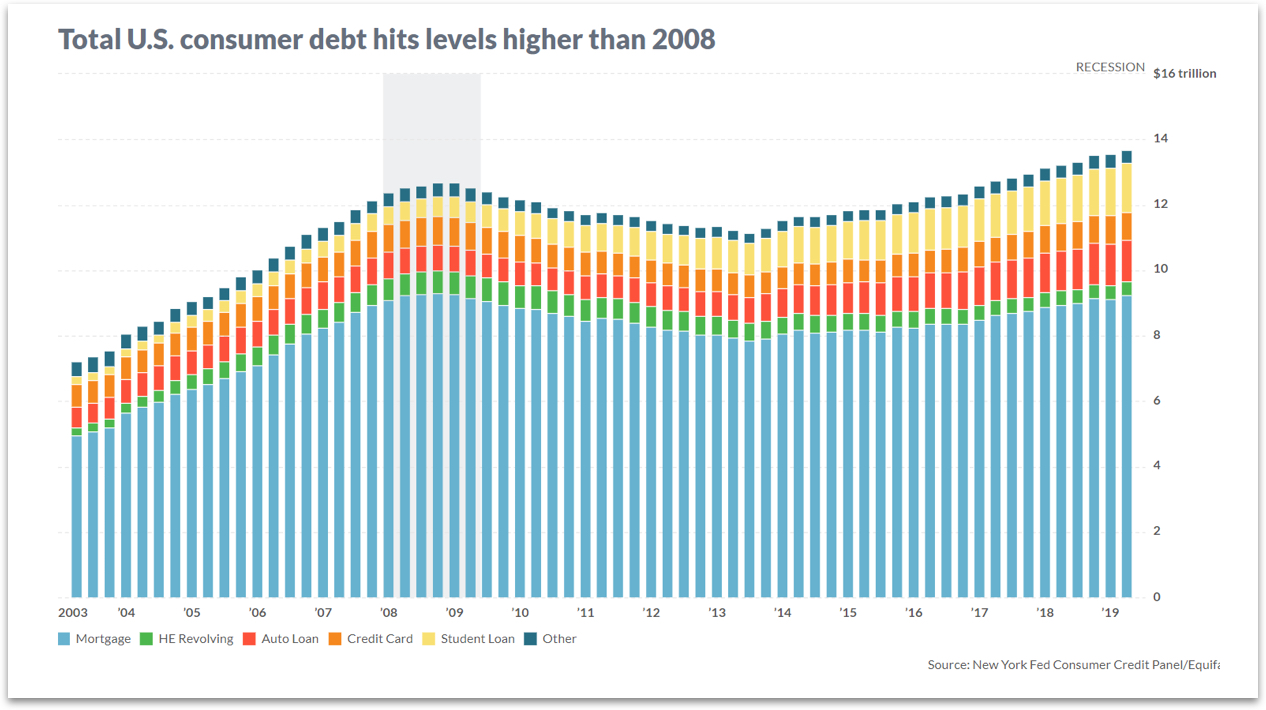

As investors are also becoming more risk averse, we may very well be headed for a consumer, corporate and sovereign debt crisis. Despite an increasing savings rate in the last decade, US consumer debt is now higher than in 2008.

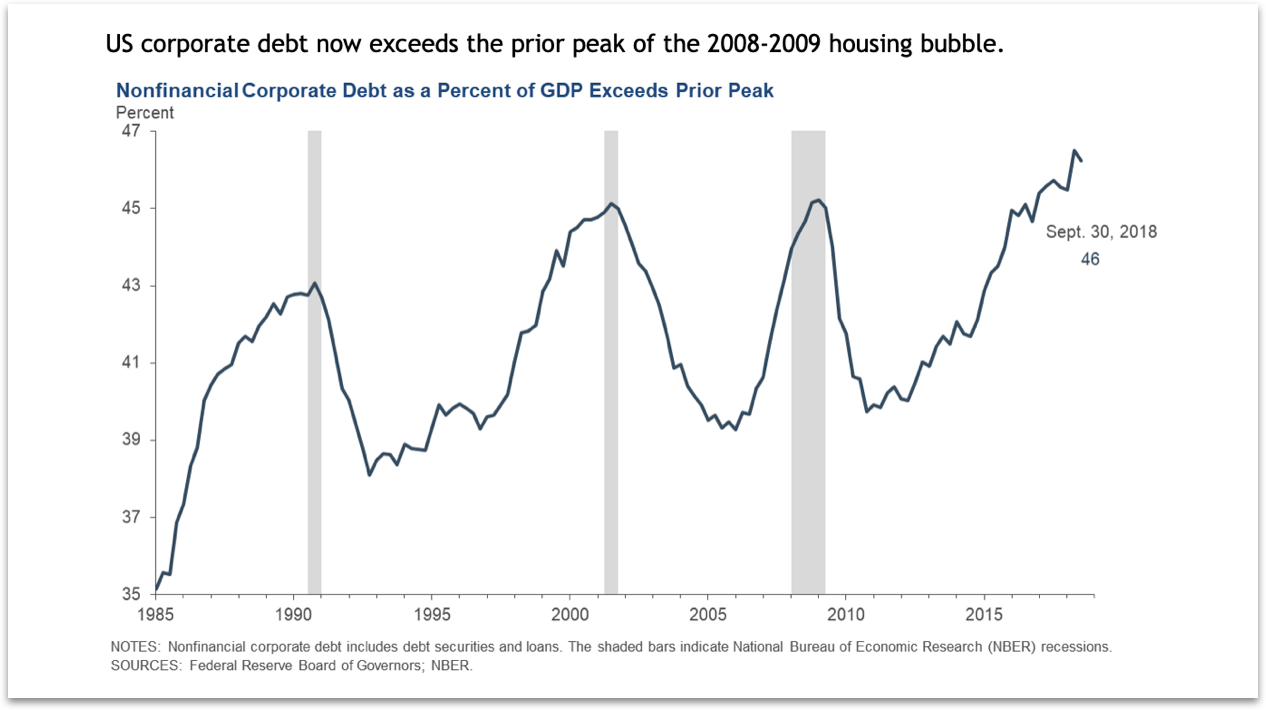

US corporate debt now exceeds the prior peak of the 2008-2009 housing bubble.

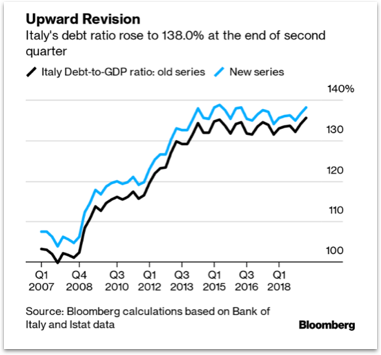

Many countries’ fiscal position worsened over the last decade. Countries have been running deficits during a long macro expansion leaving them in a much more precarious position to deal with a recession. Italy, with a debt to GDP ratio above 130%, looks particularly vulnerable. They have been badly hit by COVID-19 and as investors worry spreads with German bonds have been rising. They are also not in a fiscal position where they can afford significant loosening to fight the upcoming recession. The economy is expected to contract by at least 3% this year according to a recent forecast by Oxford Economics. On top of that the country’s banks are poorly capitalized and cannot extend credit to the country’s borrowers. Worse the banks own about a quarter of the country’s $2.4 trillion debt linking the fate of the two in a destabilizing way.

Italy is the eighth largest economy in the world and almost ten times larger than Greece which caused the last sovereign debt crisis a decade ago. An Italian sovereign debt crisis would rapidly prove contagious. Greece and Portugal are vulnerable given their high debt to GDP ratios and relatively low growth. Banks in France, Spain, Portugal and Belgium all hold substantial amounts of Italian government debt and would be terribly hit.

At this point it’s unclear how long the economy will be on lockdown to prevent the spread of the virus and how deep the recession and financial crisis will be. The financial crisis in particular has the potential to dwarf the impact of the others as consumers, corporates and governments have used historically low rates to fund themselves and may find themselves without access to credit or with much more expensive credit in the near future.

That said at this point it’s clear that most governments, central banks, the IMF and the World Bank will throw everything including the kitchen sink at this problem. The Fed, for instance, proactively cut its rate to 0% this Sunday and is currently doing quantitative easing (QE) at over 15 times the rate of previous QEs. The US Treasury is working on a $1 trillion stimulus package. Debt relief is also on the way. New York just suspended mortgage payments. The SBA will provide disaster assistance loans to small businesses affected by COVID-19. This will probably only delay the day of reckoning relative to the massive amounts of debt we accumulated but should allow this recession to be quick if the quarantines and restrictions end in the next few months. This is by no means to say that scenarios like the Great Depression or the Great Recession are not possible, but at this stage it seems like the lower likelihood outcome. Whether it happens seems mostly to be driven by how long it will take for the virus to burn out or scientists to come up with a vaccine that can be deployed widely. If it happens in the next 6 months, the downturn will be more limited, and we should recover quickly. If it takes 18 months, the outcome would be much more severe.

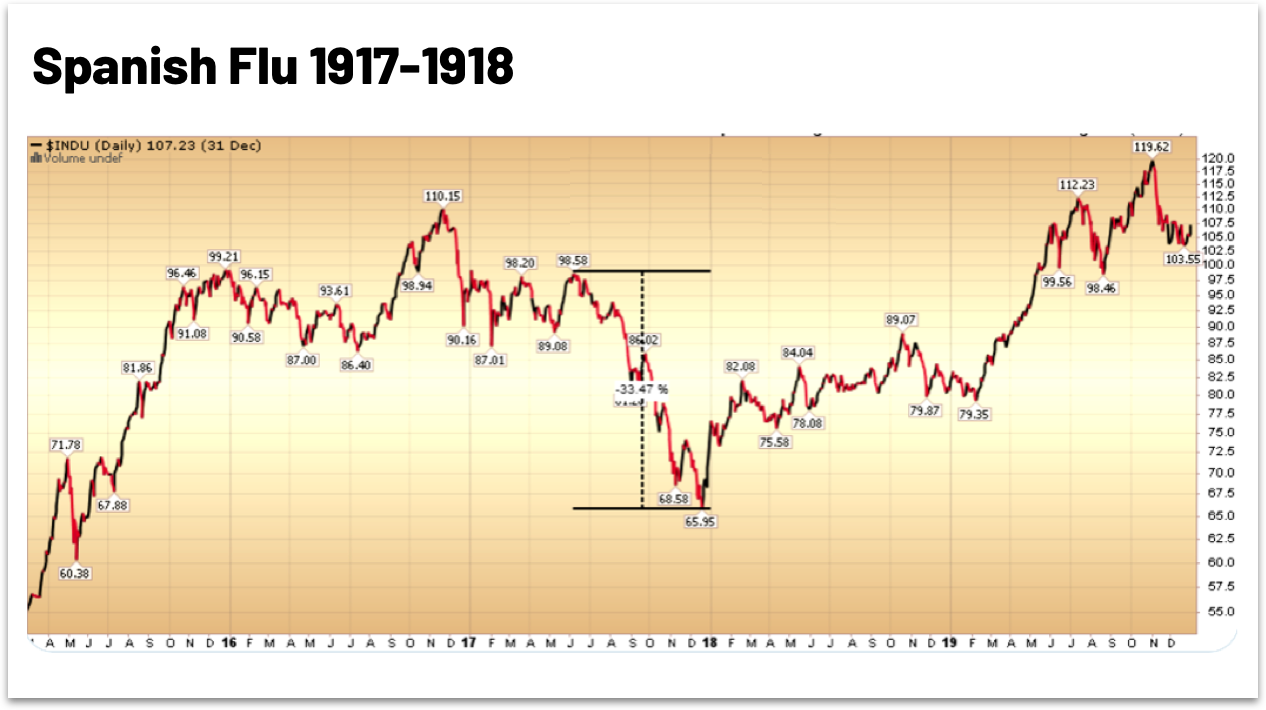

History makes me optimistic. The Spanish flu of 1918 infected 500 million (27% of the world’s population) and killed up to 100 million, or 5.6% of the world’s population of 1.8 billion at the time. Its impact and mortality were much worse than COVID-19. The economy entered a recession in 1918 and started recovering when the virus ran its course in March of 1919. Likewise, the stock market went down 35% from top to bottom in 6 months during the Spanish flu, but it took only 18 months to get back to its previous level. We may do better this time. Given the aggressive quarantine measures and all the efforts on finding a vaccine, it’s possible that the time frame will be compressed with a 3-month peak to trough and quicker recovery.

Impact on Venture Investing

Regardless of the macroeconomic outcome, I remain very optimistic about the startup sector. The Great Recession was the worst recession since the Great Depression and venture investing only decreased 27.7% between 2007 and 2009. I am especially optimistic about early stage investing. The number of angel and seed deals kept growing during the Great Recession from 457 in 2006 to 1,225 in 2009 according to Pitchbook. If an early stage startup is well capitalized for the next two years and is not in a sector disproportionately impacted by COVID-19, there is no reason not to invest. The macroeconomic environment that matters for an early stage startup is the one when it seeks an exit 5 to 10 years from now which is not impacted by the current macro environment. Said startup would benefit from facing less competition and lower customer acquisition costs as everyone is curtailing marketing spending. The same reasoning also holds true at the Series A & B though investors will be more discerning and focus on the startups that have scaled with proven unit economics, raising at reasonable valuations.

Late stage investing will be much more impacted. Exits will be delayed as buyers curtail M&A activity and the IPO window closes. Airbnb for instance will probably no longer go public in 2020. At the same time fair weather investors which have historically not been in venture investing such as Softbank, Fidelity or family offices, may very well exit the category and will at least severely curtail their investments from the 2018 high.

Which startups will be negatively impacted?

In the short term most startups will see their revenues shrink, though they should recover when the crisis ends as their fundamental value proposition has not altered. I suspect that almost all our portfolio companies will miss their 2020 plans though the distribution will not be evenly spread. Those catering to the sectors most affected by the pandemic will see bigger drops. Challenging industries include events, transportation, hotels, sports (other than esports), spas, apparel / luxury goods, restaurants and bars, construction, fitness facilities, tourism, and any business that involves physical stores or group interactions.

That said, if the startups are well capitalized and take the proper precautions, they should be ok. The ones that will be most negatively impacted fall in two categories:

1. Companies that need to raise capital now:

It’s very hard to raise capital when every investor in the world has gone risk off. We’ve already had multiple term sheets pulled near the closing date. In normal circumstances many of these startups could dramatically cut their costs to reach profitability or at least massively extend their runway, but with revenues collapsing as quickly as costs are cut, profitability will be nearly impossible to reach. Many of those startups will die.

2. Companies whose last round were highly overpriced and did not grow into their valuation:

Founders, especially first-time founders, consider the valuation at which they raise a round a badge of honor. However, the valuation that really matters is the final exit valuation, not the interim fund-raising valuations. In the frothy times of the last few years we’ve seen many examples of companies which should raise $10 million at a $40 million post money valuation (25% dilution), raise $10 million at a $100 million post money valuation (10% dilution). Intuitively if you can raise the same amount of money for less dilution it feels like you should do it. The issue is that doing so massively increases the risk that your startup will fail.

Raising at too high a valuation relative to traction is one of the most effective killers of startups. You price yourself out of exits and if you don’t grow into the valuation, given the painfulness of down rounds and anti-dilution clauses, most companies fail to raise their next round. This is especially true in the current circumstances where investors are more discerning of product market fit, unit economics and are valuation sensitive.

What should startups do?

Sequoia has a set of good recommendations for startups. The irony is that they mirror a lot of the recommendations we at FJ Labs give to our startups, even in good times. I suppose this makes us more risk averse than most, but we’ve been around long enough to know that not everything always goes according to plan.

General recommendations:

1. Raise a bit more than you need:

First time founders tend to be too dilution sensitive. They want to raise just the amount of money that will get them to the next round of funding. In good times where capital is readily available this can work, but the problem is that you may find yourself out of cash when the world is not willing to invest. We recommend our early stage startups to 18 months of runway and to know how to extend it to 24 months should it be necessary.

We don’t know how long and how sharp the downturn we are facing is. If you can raise a bit more than what you are looking for because it’s readily available, say $5 million instead of $4 million, take it.

2. Focus on your unit economics:

We’ve always been a unit economic driven firm valuing profitable growth over breakneck growth. As a result, we passed on some companies that became huge, but also avoided a much larger number that went to zero. Even pre-launch we expect our founders to articulate their theoretical unit economics based on reasonable expectations such as the industry’s average order value (AOV), recurrence and estimates of customer acquisition costs (CAC) based on some simple tests.

In general, we like businesses that recoup their fully loaded CAC in 6 months on a net contribution margin basis. We want them to 3x their CAC in 18 months. Ideally, the business has negative churn. Even though it lost say 50% of its customers after 18 months the remaining ones are buying more than double what they bought before and the ultimate LTV to CAC ratio may be above 10:1. Many of the companies we invest in have not been live for 18 months but can articulate what they think their 18 month unit economics will be given an analysis of their early cohorts in terms of CAC, AOV, churn and recurrence.

The only time we are comfortable with negative unit economics is when you can rationally articulate that with scale and density you will get to attractive unit economics.

3. Control your burn:

Note that I am defining burn as your monthly cash burn: cash in minus cash out and not just as your monthly costs.

In venture there is a reasonably clear set of expectations of where you need to be by when to raise your next round of financing. In the early days of your startup when you don’t have the scale to be profitable, your objective is to be ready for your next round. In other words, the objective of your pre-seed or angel round is to get you to your seed round. The objective of your seed round is to get you to your Series A. The objective of your Series A is to get you to your Series B. At that point you may have enough scale to be profitable and can opt to grow profitably or to raise further rounds to accelerate your growth. Some startups could be profitable earlier, but they would be the exception rather than the rule.

The expected time between rounds is 18 months. On average pre-seed or angel rounds are $1 million, seed rounds $3 million, A rounds $7 million and B rounds $15-25 million. The expected monthly Gross Merchandise Volume (GMV) traction for a marketplace startup with a 10-20% take-rate is $0 at pre-seed, $150k / month at seed, $650k / month at the A and $2.5 million / month at the B. These companies on average have a 66% gross margin.

Given that the cash is expected to get you to the next round this means you should keep your monthly burn at $50k or so after your pre-seed round, $150k after your seed, $375k after your A and $800k after your B. In other words it’s not unreasonable that if your monthly GMV is $100k / month, you are burning $100k / month, if your monthly GMV is $500k / month you are burning $200k / month, if your monthly GMV is $1M / month you are burning $400k / month if your monthly GMV is $4M / month you are burning $800k / month.

Note that these are averages and there are many outliers in both directions. A second time founder will probably command higher prices in the early stages. A company doing exceptionally well and growing faster than the norm may have a Series A that looks more like Series B. In other words, venture fundraising outcomes don’t follow a normal Gaussian distribution curve. The middle is much fatter and there is a wide dispersion of outcomes.

Note that the numbers would also be fundamentally different for a marketplace with a 1% take rate. The GMV would have to be much higher to reach similar net revenues. Inversely a SAAS (software as a service) startup with a 90% gross margin would need much lower revenues to have similar net revenues. A marketplace startup with $1 million in GMV, a 15% take rate and a 66% gross margin generates $99k in net revenues. That’s essentially the same as SAAS startup generating $110k / month in revenues with a 90% gross margin. In other words, $100k / month in SAAS revenues is enough traction to raise a Series A while a marketplace startup typically needs upwards of $650k / month in GMV.

While this is a rule of thumb, even avoiding outliers, this needs to be taken with a grain of salt. For instance, for a B2B marketplace with signed contracts coming online in the coming year, you can give them credit for some of that growth and justify a Series A even if they are not yet at what would otherwise seem to be sufficient traction..

For simplicity I put together this little cheat sheet.

Specific recommendations for the current times:

1. Expect your revenues will decline:

Many businesses are essentially shut down right now given both supply chain disruptions and worker quarantines. Even if you could serve your customers, they would probably curtail their spending. At the same time if you are sales driven, you should not expect to be able to meet and close new deals for months. Even deals you were convinced were going to close will at least be delayed if not outright cancelled.

2. Delay hiring and investing until it hurts:

It’s a good rule of thumb for startups to delay hiring until it hurts and to remain very cash conscious, but even more so in these times. It’s also worth revisiting capital spending plans to make sure they are appropriate considering the current environment.

3. Cut costs:

It going to hurt, but it’s a good time to trim all expenses. It’s the perfect time to try to increase productivity and do more with less.

Exceptions

If you are in an industry that benefits from the crisis such as online education, remote work technologies, or online entertainment, now is a good time to be investing. This is also true in other industries if you have an exceptionally strong balance sheet and lean cost structure. You can take advantages of lower customer acquisition costs while others retrench, or you can acquire weaker competitors.

What’s important is to be deliberate about your spending choices rather than just follow whatever plan you originally put together before the crisis occurred.

What should venture funds do?

Many entrepreneurs don’t understand why venture funds stop investing in down cycles even though the macroeconomic environment that matters is the one that exists when they try to exit 5 to 10 years in the future. The reason is related to the way venture funds get their own capital. Venture funds have partners who make investment decisions, they are called General Partners or GPs. They deploy capital that is given to them by Limited Partners or LPs. These are typically pension funds, university endowments, family offices and the like.

The GPs typically charge a 2% annual management fee and 20% carry (20% of the profits) over the 10-year life of the fund. When it’s announced a fund raised a certain amount, say $300 million, they don’t have the cash on hand. Instead they call the capital when they need it from their LPs to cover fees and investments. A typical $300 million fund only has $240 million to invest because 20% of the capital (2% per year for 10 years) is reserved to pay the fees of the GPs that covers their cost structure: salaries, travel, rent, events etc.

A typical $300 million fund might deploy $80 million per year over 3 years calling $86 million per year (including fees) in multiple capital calls. Once the fund is fully deployed after the third year, the remaining calls would be to cover $6 million annual management fees. Once successful exits start occurring and the LPs recouped their $300 million, the GPs would also take 20% of the profit.

Typical institutional investors try to create balanced portfolios. They may want 10% in private equity and venture capital, 40% in equities, 20% in bonds, 20% in real estate and 10% in cash. The issue is that when public securities holdings crater, the portfolio looks unbalanced from their perspective because private assets are rarely repriced so suddenly, they might find themselves, on paper, with much larger exposure to venture capital than they want. If you do a capital call at that point in time you would only exacerbate their portfolio imbalance. Many LPs request that you don’t call capital in those times as they might not be able to fulfill them, especially if they find themselves short on cash, perhaps because they were trading on margin and are facing capital calls from their banks.

I’ve argued in the past that this traditional portfolio construction is flawed at the individual level preferring bar bell investing with lots of cash on hand to take advantage of opportunities in downturns and a very diversified portfolio of startups on the other hand. This is also true at the institutional level. VCs should try to be counter cyclical rather than pro-cyclical. Some of the best companies are created in a time of crisis.

For instance, the following companies were founded between 2008 and 2009 during the financial crisis: Airbnb, Cloudflare, Github, Pinterest, Slack, Square, Stripe, Uber and Whatsapp. If you stopped investing in that time period, you missed out on the best and most defining companies of the last decade.

At FJ Labs, we are still seeing many exciting opportunities. We’ve increased our investment threshold, narrowed our focus to early stage marketplaces which raise enough to withstand the coming storm, but are still committed to investing. Times like these, and our nontraditional approach to venture investing, are the reason we avoided traditional institutional LPs in favor of a limited number of strategic LPs who understand the opportunities created by the circumstances we find ourselves in.

Conclusion

We don’t currently know the duration and severity of the upcoming downturn and a wide range of outcomes is possible. However, based on the aggressiveness of policymakers’ initial response, it seems like the downturn, while severe, may not be prolonged. A scenario like the one of the Great Recession or Great Depression, while not impossible, seems to be on the lower probability end of the spectrum, especially if COVID-19’s impact on our life ends in the coming 6 months. This is all the truer as policy makers are applying the playbook they devised after the Great Recession with the lessons learned during that crisis.

Startups will face difficult times in the coming year and those that need to raise capital now may very well die. For those that adapt and withstand the storm and for those created in these times of crisis, the future is bright. The technology sector will remain the engine of productivity and economic growth and its influence will only be magnified. The pandemic is accelerating the shift towards online ordering, online consumption and the shift to remote and flexible work. There is much room to grow. We are still at the very beginning of the technology revolution. Only 15% of commerce is online. Online penetration remains negligible in the sectors that account for most of GDP: education, health care, and public services, but as these services have started to migrate online during the pandemic, a tidal wave of change is coming.

Technology will finally exert its deflationary power while improving user experiences in more areas of the economy. We live in challenging times, but they are also exciting as we are starting to build a better world of tomorrow, a world of equality of opportunity and of plenty!