Hang around venture capitalists in Silicon Valley and a clear sense of fear pervades the air. The main topic of conversation these days seems to be of humbled or fallen unicorns. Many are writing down the value of their holdings. This correction is driven by the impact of global macro changes on the late stage funding environment.

We are currently observing a debt crisis in emerging markets.

We had a first debt crisis in the US when a glut of global savings, much of it from Asia, washed into subprime housing, with disastrous results. In the euro area, thrifty Germans helped to fund booms in Irish housing and Greek public spending. As these rich-world bubbles turned to bust, sending interest rates to historic lows, the flow of capital changed direction. Money flowed from rich countries to poorer ones. This led to another binge with too much borrowed too fast with lots of debt taken on by firms to finance imprudent projects or purchased overpriced assets. Overall debt in emerging markets has increased from 150% of GDP in 2009 to 195% today. Corporate debt has surged from less than 50% of GDP in 2008 to 75%. China’s debt-to-GDP ratio has risen by nearly 50 percentage points in the past four years.

Now this boom too, is coming to an end. Slower growth and weak commodity prices have darkened prospects even as a stronger dollar and the approach of higher American interest rates dam the flood of cheap capital. As companies and countries need to deleverage slower growth lies ahead in emerging markets.

This actually makes the US, and startups in the US, more attractive from an investment perspective. However, this is dwarfed by its negative impact on the late stage venture market.

The late stage venture market has changed because companies are staying private longer.

Companies used to go public once they were worth a few hundred million dollars.

IPO Market Capitalization:

- Microsoft (1986): $500 million

- Yahoo (1996): $850 million

- Amazon (1997): $440 million

If anything Apple’s market capitalization of $1.78 billion at IPO in 1980 was the exception. These days the very best companies stay private much longer. Facebook went public at a $100 billion valuation in 2012, 8 years after it was created. Alibaba Group went public in 2014 at a $225 billion valuation, 15 years after its creation.

According to the NVCA, the average time for a venture-backed company to IPO has gone from 3.1 years in 2000 to 7.4 years in 2013. The very best companies like Uber and Airbnb are raising money at tens of billions of dollars in valuation to stay private longer. If anything the companies that are going public at $1-$5 billion valuations like Box and Square seem to be the ones that have no financing alternatives.

This makes eminent sense. The explicit and implicit costs of going public have increased dramatically. As an Internet entrepreneur I used to dream of taking my company public. No longer!

- The regulatory and compliance burdens have increased dramatically especially since the Sarbanes-Oxley Act («SOX») was passed in 2002. It adds layers of bureaucracy, time, and costs which makes it harder to “move fast and break things.»

- The process for going public is painful and extremely distracting.

- Analyst coverage and liquidity for companies worth less than $2 billion is limited.

- You have to share more information about your strategy that your private competitors can take advantage of.

- The need to “hit the numbers” makes it hard to experiment with new business models or to cannibalize your own business even if it’s the logical business decision.

At the same time, the cost of staying private longer have decreased dramatically:

- There are more sources of capital to late stage companies than ever before. Traditional VCs have raised large funds forcing them to invest at later stages. Non-traditional actors like hedge funds, mutual funds and family offices are also investing in late stage private companies.

- Investors are offering founders and employees partial liquidity either in financing rounds or through platforms like SharesPost and Equidate.

Because most of the value creation has been accruing to private investors, public market actors entered the market pushing valuations up.

The value that used to accrue to public investors (e.g.; Microsoft’s increase in value from $500 million to $336 billion) is now accruing to private investors. Public investors in Facebook only saw a 2.2x return from $100 billion to $220 billion. Private investors at every stage got the vast majority of the upside. As a result, public market actors like Fidelity and T. Rowe and hedge funds like Coatue and Tiger Global felt they had to enter the venture market.

Every year around $50 billion is invested in venture in the US. However, that is dwarfed by the trillions on the balance sheet public market actors. The only place where public market actors could deploy enough capital to move the needle for that was in later stage private companies.

The problem is that, startup success, like venture returns, follows a power law. There are very few billion dollar companies created. With much more capital, chasing the same few companies, valuations soared.

Public market actors are impacted by the debt crisis in emerging markets forcing them to pull back on their private investments, taking the froth out of the late stage market.

By definition most of the money managed by public market companies goes to the largest companies by market capitalization. These companies are typically global. They are seeing their profitability, and hence stock price, hit by the double whammy of slower growth in emerging markets and the strong dollar. As these large companies account for most of the value in public markets, the markets are down for the year as a whole.

As hedge funds and mutual funds try to keep their private portfolios below a certain % of their overall assets under management, they have to make fewer, and perhaps even divest, private investments. This would be even more true should the current volatility lead to a wave of redemptions. To fund redemptions, they would sell their public market securities. They would then face pressure to decrease their illiquid private exposure.

As a result, except for the very best late stage companies like Uber and Airbnb, it’s going to be harder to raise for late stage startups.

That said, this feels more like 1998, than 2000!

In 1998, like today:

- There was an emerging market crisis (1997 Asian Financial Crisis and 1998 Russian debt default)

- Hedge funds were blowing up, LTCM in particular almost blew up the financial system

- The US was the engine of global economic growth

- Pundits were worried about startup valuations with Alan Greenspan famously fretting about irrational exuberance

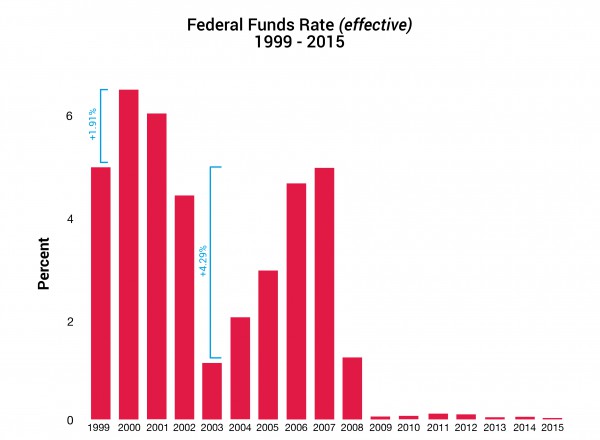

Interest rates were lowered to fend off the crisis and capital rapidly flowed to the US. The real day of reckoning only occurred two years later after the bubble really inflated, and after interest rates were increased 191 basis points.

Barring exogenous “black swan” shocks, the conditions are set for the startup party to continue.

It may very well be healthy for fear rather than greed to be current primary motivator of investors as it pushes companies to focus more on their business models and to have more reasonable burn rates. Taking a step back, I suspect that this transition to fear is going to be temporary as the underlying macro principles that underpinned the startup boom are still in place:

- Interest rates are still 0

- The technology sector remains the largest creator of productivity and job growth

- Investors are still yield chasing, especially in safer geographies like the US

- Entrepreneurs now have access to billions of global customers through smart phones and the web allowing massive companies to be created faster than ever before in the history of time

- Technology improvements and adoption (smartphones with GPS, decreases in sensor, storage and computing power etc.) are such that we are on the cusp of a technology revolution in almost every sector that has not yet been touched by the technology revolution including education, medicine and transportation.

- Even industries that felt they were immune to the digital revolution are going to be revolutionized (e.g.; your neighborhood massage parlor or dry cleaner)

The current late stage venture market correction will lead to the death of a number of well-known unicorns who fail get their unit economics to work and decrease their burn rates quickly enough. However, in general, we are still at the very beginning of the Internet revolution. It’s going to create lots of growth and value. The capital to make it happen is available.

Capital might become more scarce in the future, but it’s going to take at least 100 basis point increase in interest rates before we start seeing it filter down the system. As is it does not look likely to happen before 2017 or 2018.

Party on! (but pay attention to your unit economics and burn)