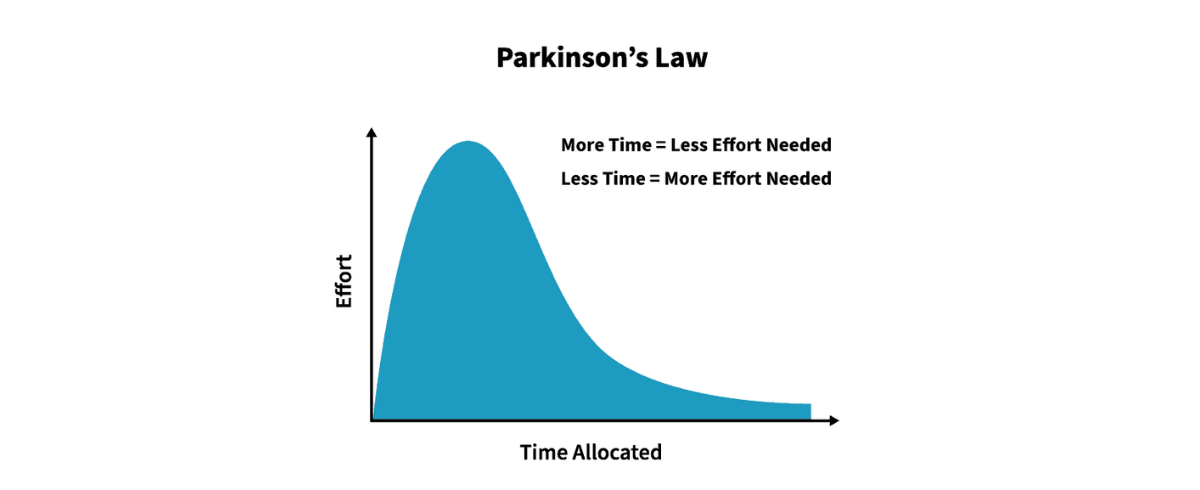

Parkinson’s Law states that “work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion.”

“Thus, an elderly lady of leisure can spend an entire day in writing and dispatching a postcard to her niece at Bognor Regis. An hour will be spent in finding the postcard, another in hunting for spectacles, half-an-hour in a search for the address, an hour and a quarter in composition, and twenty minutes in deciding whether or not to take an umbrella when going to the pillar-box in the next street. The total effort which would occupy a busy man for three minutes all told may in this fashion leave another person prostrate after a day of doubt, anxiety and toil.”

Interestingly, Parkinson observed a similar manifestation in the British Civil Service, noting that as Britain’s overseas empire declined in importance, the number of employees at the Colonial Office increased.

According to Parkinson, this is motivated by two forces: (1) «An official wants to multiply subordinates, not rivals» and (2) «Officials make work for each other.» He also noted that the total of those employed inside a bureaucracy rose by 5-7% per year «irrespective of any variation in the amount of work (if any) to be done».

The analysis first appeared in an article in The Economist in November 1955 and was then articulated in a book Parkinson’s Law: The Pursuit of Progress, (London, John Murray, 1958).