By Jeff Weinstein and Luke Skertich

Background

Early-stage venture capital has undergone a seismic transformation over the past decade as companies stay private longer, raise more capital and exit for larger magnitudes. (NB: the SPAC mania of 2020 may alter this trend, but for now these phenomena still hold). According to SVB, the average VC-backed company at time of IPO in 2018 raised $184M across six rounds, up from $60M across four rounds in 2010. And the average length of time from founding to IPO doubled to 12 years. Meanwhile, valuations have increased accordingly, with 22 $1B+ valuation tech IPOs in 2020 to-date, up from 3 in 2010.

With startups staying private longer and growing larger, Seed and Series A venture investors have come across an interesting dilemma: with limited reserves to follow on across multiple financing rounds, what should they do with their pro ratas in their breakout portfolio companies?

Enter the opportunity fund: a new fund structure soaring in popularity among early-stage GPs that offers an elegant solution to this problem. Done properly, an opportunity fund — sometimes known as a “select fund”, “follow-on fund” or “growth fund” — offers fund limited partners (LPs) the prospect of doubling down on emerging winners in a fund’s portfolio. Per Pitchbook, there have been over 300 “opportunity funds” or “select funds” raised since 2010. However, some LPs have pushed back on this structure, feeling that it serves as an easy way for general partners (GPs) to gather AUM and a distraction from their job of managing a Seed-stage portfolio.

At FJ Labs, we currently angel invest from one fund across different stages, and we have been studying whether it makes sense to silo our investments into an early stage (Pre-Seed-A fund) fund and a Growth/opportunity fund. My research partner Luke and I were shocked by the dearth of available literature on the subject; virtually no one has published any articles or papers on opportunity funds, perhaps because of how new they are. So we embarked on a journey to interview some of the premier early-stage fund managers who have pioneered these vehicles and the LPs who evaluate and invest in them. We surveyed over 30 venture capital managers ranging from Seed stage to pre-IPO, and LPs ranging from family offices to fund of funds to state retirement plans. We left with a thorough understanding of best practices in structuring growth/opportunity funds and reached a high-conviction conclusion for how we should structure our next fund(s).

Methodology

We approached this like a research project. We began by reading ~50 blogs, academic papers & research articles. We made it a point to understand divergent schools of thought regarding portfolio construction — spray and pray, algorithmic, concentrated — because it helps underscore why VCs and LPs alike have focused their energy on opportunity funds. Our reading ranged from early-stage investment best practices to Abe Othman’s amazing posts using AngelList data to growth equity best practices. This research culminated in an understanding of who we wanted to interview and what questions we would need to have answered.

We laid a foundation by benchmarking fees and returns and layered on an understanding of follow-on investments, conflicts of interest, and capital allocation. Next, we dove into why firms created their opportunity funds, how LPs viewed them, and how they’ve performed.

Finally, we created a functional fund model, utilizing FJ’s current portfolio to inform it. We’ll share a more simplified and generalized model, below.

General Context

So, what are GPs and LPs saying about opportunity funds more broadly? We’ve gathered a select handful of quotes to set the stage…

“LPs don’t love opportunity funds. They want true seed risk.” — GP

“We are more time-constrained than cash-constrained. We can’t invest in 2x the number of companies, so this is a way to cram more dollars in companies we’re excited about.” — GP

“Generally speaking, we try not to do opportunity funds.” — LP

“Some opportunity funds have outperformed their core funds!” — LP

Findings

Portfolio Construction

“Most opportunity funds are more concentrated because you’ve had a filter or two against the investment set.” — LP

While there are differing opinions on optimal portfolio construction at the early and growth stage, there is consensus that opportunity funds should consist of six to ten unique positions. The number of investments is informed by the number of prior investments across funds for each GP. In other words, an opportunity fund is a mechanism for GPs to double down on the top 5% of their investments. Likewise, LPs obtain access to the best investment opportunities and benefit from their GPs’ insider information on their portfolios.

Why not raise a bigger fund?

Separate funds enable GPs to write larger checks in their emerging, later-stage winners without diluting their early stage portfolio. However, writing large checks from one fund may lead to LP concerns regarding style drift (“We invested in you as a Seed fund manager”). Providing LPs with two tightly-defined products with specific risk/reward profiles can more effectively cater to their needs.

Additionally, some LPs can’t evaluate individual co-investment opportunities and would prefer to participate in a “best of” style opportunity fund. In effect, LPs get access to all follow-ons, rather than select investments via SPVs, and from a GP perspective, this is far more convenient to administer than ad hoc SPVs.

While there is precedent for Seed-to-IPO funds like Insight Partners and NEA, trying to expand beyond the early stage requires a change in firm strategy. This is not the case with opportunity funds, which are typically more passive, follow-on vehicles (as we’ll discuss below, opportunity funds should not lead, running counter to multi-stage fund strategy). If you plan to remain an early-stage investor, the opportunity fund is the right vehicle for you to double down on winners. If you want to create a franchise that invests across all stages, then it makes sense to explore a multi-stage fund.

Fund Economics

“We invest for 20% IRR regardless of the asset class. A good opportunity fund is 2X net, 20% IRR. — LP

“If you can return 2X net to your LPs w/ 20% gross IRRs, you can raise capital forever” — GP

Our survey confirmed that venture investors and LPs target a 3X net fund return across early-stage, growth stage, and opportunity funds. However, we also learned that if VCs can achieve at least 2X MOIC returns or 20%+ IRRs, they will be able to keep raising funds for years to come. Opportunity funds are measured against the same benchmarks. However, given how new these vehicles are, we don’t have comprehensive data on their performance.

While return expectations are the same, fee structure differs by fund type. We did not come to a consensus on fees and carry for opportunity funds. That said, there is agreement that whatever your fees and carry on your early-stage fund, you should take less on the opportunity fund. Otherwise, LPs will feel that you are taking advantage of a new vehicle to increase AUM. Perhaps this is why it is seen as best practice for GPs to only take fees on invested capital from the opportunity fund (vs. on committed capital for traditional funds).

Follow-ons and Leading

“Only invest in companies that are outside-led growth rounds that are growing 2X a year.” — Opportunity fund GP

“If I could go back to the beginning of my career, I’d say the one thing to know is the magnitude of exit will get bigger by another standard deviation.” — LP

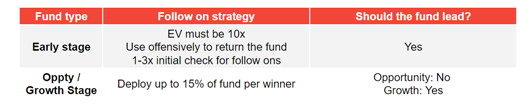

Follow on strategy begins with doubling down on winners. Best practice indicates that GPs should not use opportunity funds to protect existing investments, should not lead investment rounds with their opportunity funds, and should create systematic rules for which fund (early-stage vs. opportunity) gets pro rata rights.

Most commonly, use of pro rata rights is separated by investment stage. For example, an early-stage fund may invest until Series B, at which point an opportunity fund invests in Series C+. This cutoff can be delineated by round size, valuation, or some combination. It is wise to have clearly defined rules around selling secondaries, down rounds/pay to play mechanisms, bridge rounds, incubator/accelerator companies (if your firm has one), etc. Often, managers will consult with their Limited Partner Advisory Committees (LPAC) for edge cases or complex scenarios.

LP Preferences

“Managers often ‘staple’ funds together: if you want access to a Seed fund, you have to invest a ratable amount in that manager’s opportunity fund. However, it is important for VCs to only do this practice with new LPs.” — GP

“Ultimately, a lot of these get raised on how sexy the GP is.” — LP

We found that LPs don’t like being stapled but often don’t mind insomuch as they are granted early-stage fund exposure. Some firms use formulas to give larger / more loyal LPs higher allocations in early-stage funds. Interestingly, while LPs are thought to hate opportunity funds, we did not observe overwhelming distaste for them among our interviewees. Rather, we found that the jury is still out until we can see widespread data from the past ten years.

Nor did we come to a firm conclusion if LPs preferred individual co-investment opportunities versus an opportunity fund that aggregates them. Some more nimble LPs such as family offices like to participate in direct co-invests, while other, slower-moving institutions prefer for the manager to do by follow-on investing via an opportunity fund.

Additionally, LPs had differing opinions on participation in opportunity funds, depending on the risk/reward profile they were looking for. Institutional LPs will typically view opportunity funds more favorably, as will any LPs looking for a shorter time to liquidity.

Fund Model

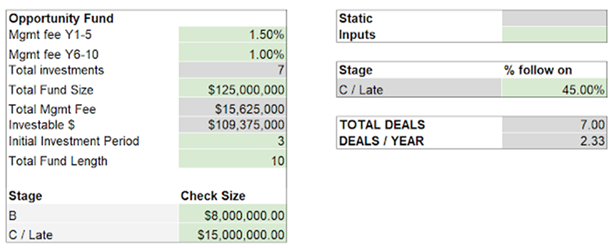

We mentioned earlier that the opportunity fund model is informed by prior fund construction. We simplified and generalized our model to demonstrate this:

In this case, we wanted to end up with an opportunity fund that supports two 30-company early-stage funds. Assuming that the top 10% of companies across these funds will be breakouts, that implies a portfolio of ~6 companies. You can adjust the inputs to tailor the fund construction given your portfolio makeup and investment pace. You can also back into the correct check sizes (for each stage) by examining your pro-rata rights and ownership across the portfolio. You should raise this fund with certain portfolio company high-flyers in mind, but do not advertise your fund as if you will have guaranteed allocation.

Conclusions

Opportunity Funds allow LPs to titrate their risk exposure and for GPs to provide more tightly-defined products to effectively cater to their investors’ needs. They are easier to administer and capture more value than ad hoc SPVs, which run a higher risk of losing LP capital and have to be spun up one-by-one. If investors separate funds, they can write large checks at later stages without diluting their early-stage investments.

Opportunity fund LPs are typically satisfied with returns of 2X Net MOIC and 20% IRR. Opportunity funds typically focus on existing portfolio companies and are run by existing investors, whereas growth funds are typically run by separate teams and focus on new investments. There is an expectation that opportunity funds carry lower fees and run a more concentrated portfolio than early-stage funds.

Unfortunately, there is not enough public data to evaluate their returns to-date, but judging from their proliferation and the expansion of venture capital as an asset class, we suspect opportunity funds are here to stay.

—

Jeff Weinstein is a Principal at FJ Labs, an early-stage venture fund and startup studio that invests in and builds online marketplaces. Jeff co-heads the fund’s 500+ investments which have included Alibaba, Flexport, Rappi, Betterment, Fanduel and Delivery Hero, and also manages FJ’s external fundraising efforts. Jeff was previously a Senior Associate at Lux Capital, and prior to that worked at a fund of hedge funds. Jeff is in Class 24 of the Kauffman Fellows.

Luke is an MBA candidate at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business with concentrations in Finance, Entrepreneurship, and Strategic Management. In addition to his work with Jeff at FJ Labs, Luke is an Associate at M25 in Chicago, where he focuses on investing in early-stage startups. He previously worked as a Product Manager at three B2B tech start-ups in Chicago, spanning the benefits administration, fintech and human capital management spaces.

Thanks Jeff, this is really helpful!