Eighteen months ago, I was contacted by my good friend Kevin Ryan who invited me to join him on a scientific expedition skiing to the South Pole. In exchange for sponsoring the expedition a select crew of sponsors got to tag along and partake in the adventure. He was looking for the Venn diagram intersection of the people who could afford it, were fit enough to do it, and just as importantly would be interested in such a crazy adventure. I must admit I was not quite sure what the trip entailed but being a sucker for adventure and new experiences I immediately signed up. This turned out to lead to the most extraordinary of adventures.

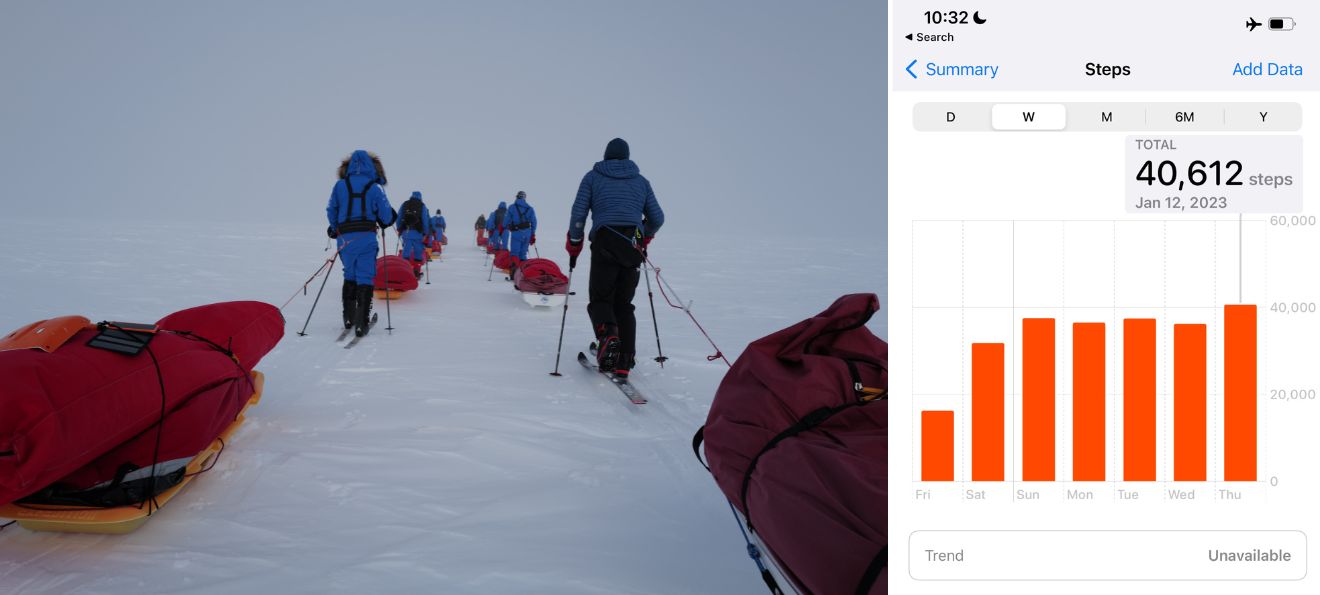

The expedition started with training in Finse, Norway in March 2022. There were plenty of skills to learn: how to pack our sleds, assemble our tents facing the wind, melt snow to cook our meals, even learn how to walk with these special skis with half skins to be able to pull our 100-pound sleds. Perhaps most importantly we needed to acquire and learn to use all the equipment we would need for the expedition. You can see the seemingly infinite list on pages 34-46 of the instruction pack embedded below. As you can imagine given the expected cold layering up and down effectively is key.

It’s during the training that I met Dr. Jack Kreindler . He was one of the scientists who came up with the idea for the expedition as a scientific research study. It stemmed from a 2017 (all men) and 2019 (all women) British coast-to-pole military expedition during which many of the super fit male soldiers in the first expedition struggled, while the all-women group did well. They showed early evidence that women did better than men because they lost less muscle mass. Dr. Jack and colleagues wondered if there was a way to tell what caused this difference and to know ahead of time who was going to do well or not in such hyper-endurance challenges using wearables. This new study, the Interdisciplinary South Pole Innovation & Research Expedition, was the largest of its kind in extreme environments. It was composed of two teams: a 10-person team doing the 60-day 1100 km coast-to-pole expedition INSPIRE-22, mostly military types, half female and half male, half on a vegan diet and half on an omnivore diet. The other INSPIRE Last Degree 23 composed of a team of eight sponsors and two scientists including Dr. Jack and Dr. Ryan Jackson, skiing the Last Degree, 111 km unacclimatised going from 89 degrees south to 90 degrees south. This also allowed the team to test how quickly our bodies adjust to this extreme environment given that we would be on the ice for 10 days relative to the 60 days of the coast-to-pole team. Our challenge was made more difficult by the fact that we started at a 10,000 feet elevation while they started at sea level and would get the opportunity to adjust to the altitude over time.

The training involved skiing up to 16 miles or 25 km per day while pulling a 100-pound sled in blizzard conditions, sleeping in freezing tents, eating dehydrated food, with only a shovel as a restroom. It was painful, cold, and difficult, and yet I loved it. Many questioned why I was doing something so challenging, which prompted a period of reflection as to my motivations. Ultimately, it culminated in the blog post Why? where I articulated why I love putting myself in challenging situations, depriving myself of the very things I am thankful for, and risking losing it all.

I recommend you read the entire post, but the quick summary is as follows:

- A love for flow states.

- A sense of meaning ingrained in the human condition.

- Gratitude practice.

- An openness to serendipity.

- New learnings.

- Clarity of thought.

- Staying grounded.

My conclusion from the training was that the expedition would be very challenging, but doable. I decided to make sure I was in great shape before heading to Antarctica. I started doing strength training three times a week, did 2-3 hours of exercising per day, almost every day, mostly kiting and padel in November and December, and lost 25 pounds.

I flew to New York to Santiago the night of December 30th and continued to Punta Arenas the morning of December 31st. Punta Arenas is Southernmost part of Chile and serves as the pre-staging area for expeditions. It’s there that I met the other team members for the last degree:

- Taavet Hinrikus, founder of Plural and Transferwise.

- Jena Daniels, VP at Medable.

- Arnis Ozols, co-founder of Aleph.

- Ivan Cenci, general manager of Empatica.

- James Berdigans, founder of Printify.

- Nicolas Ryan-Schreiber, founder of Aym and Kevin Ryan’s son.

In total there were 10 of us and were joined by three guides who would lead the expedition. I must admit that I thought it odd that we needed to be in Punta Arenas on December 31st rather than with our families, but the window for a polar expedition is very brief given how short the polar summer is. Every year they set up the camp at Union Glacier mid-November, only to take everything down again January 20th. During that time frame ALE flies 500 people to go on expedition and can only accommodate 70 guests at a time, leading to a compressed schedule.

Punta Arenas is a mining town of 125,000, but I suspect that many people don’t live there full time as the city was entirely deserted. I often felt as though I was in The Last of Us given how empty the streets were. There were also no new year celebrations other than the muted horns from the transport ships at midnight.

Regardless, I was happy to meet my expedition mates. During the next three days, we did daily COVID tests, checked our gear, made final equipment purchases, and did a battery of blood tests to get a baseline for where we stood prior to the expedition. We were also fitted with blood glucose monitors, Empatica medical devices and Oura rings.

On January 3, we finally flew to Union Glacier station in Antarctica which was our staging area for the expedition. We bid our farewells to civilization and boarded ALE’s Boeing 757. As we neared Antarctica, they turned off the heat in the plane to get us accustomed to the temperature on arrival. The most impressive part of the flight was the landing on the blue ice runway.

Upon arrival, we were transported on tracked vehicles to the station. The station has 35 two-person tents for guests, tents for the staff as well as all the necessary support infrastructure: a dining hall, meeting hall, a pantry, medical station etc.

Upon seeing the infrastructure, I started to appreciate why Antarctica is so expensive. The season is only 2 months long. Everything must be assembled and de-assembled every year. All the food and staff must be flown in, and all waste is flown out, including all human waste.

Union Glacier itself was quite pleasant. We were staying in large pre-installed tents that have foldable beds you can put your sleeping bag on. It’s in the western part of Antarctica on 1,500 meters (1 mile) of ice. Relative to the polar plateau, the weather was a balmy -5 degrees.

It attracts a lot of adventurers preparing for various expeditions. Through sheer serendipity I ran into my friend Chris Michel, photographer extraordinaire whom you can thank for many of the more beautiful photos in this post. I also ran into Alex Honnold of Free Solo fame.

While at Union Glacier, we did a refresher on our training. We then picked 10 days of food for the expedition consisting of two high calorie rehydrated meals per day (breakfast and dinner) and enough snacks to get us through 8 rest stops, during which we must eat, per day. We packed our sleds and awaited favorable weather conditions to start our journey.

While waiting for the expedition to begin, we did a fat bike tour. We did a hike to “Elephant Head”. We also watched ALE’s Ilyushin IL-76 Russian transport plane land on the blue ice which was rather impressive.

The weather finally cleared on January 6, and we were set to embark on our expedition. We loaded our gear on a DC3 from 1942 and were dropped off at 89 degrees south to begin our journey. The time had come. Our lifeline to civilization now gone, we were henceforth left to our own devices. We could only rely on ourselves for the days to come. All the problems of the world at bay, only one thing mattered: reaching the pole safe and sound.

Antarctica is the land of superlatives. It’s the highest, coldest, and driest continent. Nowhere is it more apparent than on the polar plateau with 10,000 feet of ice below your feet and a seeming infinity of whiteness in every direction. It often feels as though you are walking on clouds.

The first day we decided to only do two legs before setting camp to acclimate to the altitude and conditions. On the second day we did 6 legs before settling into a routine of 8 legs per day. The schedule was as follows: we would wake up at 7 am, have breakfast, pack our camp into our sleds, then ski for 50 minutes, then take a 10-minute break 8 times in a row, averaging 13 miles per day, before setting up camp again, having dinner and settling in for the night.

For the last frontier we were skiing 69 miles or 111 km to the pole. When we learnt it was that short, Kevin and I thought it would be super easy, barely an inconvenience, and that we would be done in 5 days. We did not understand why we were planning to take up to 10 days. After all we routinely hike 15-20 miles in a day carrying our camping gear.

Needless to say, our expectations were way off. It was significantly harder than we ever expected and definitely the hardest adventure either of us had ever been on. I suppose it’s due to a combination of factors: the altitude, the exertion of doing an activity we are not familiar with, pulling a 100-pound sled, and the cold. The temperature was a constant -30 degrees whether day or night and required constant care to make sure we were not cold, but also that we did not sweat during the walking section which would lead us to freeze during the breaks. The dry -30 was reasonably easy to manage, but what would alter the conditions dramatically was whether there was wind or not. Several of the days we had wind essentially straight into us bringing the windchill to -50. In these conditions you cannot expose any skin as it would lead to frostbite and the potential loss of limbs.

The first few days I struggled to keep my fingers warm. They were always in dire pain and burning. However, as I learnt, pain is your friend as it means blood is still reaching your extremities. It’s when you stop feeling the pain that you are actually in trouble. In one of the other groups, one of the guests forgot to bring up his fly after peeing. They had to cut off three inches from his penis.

The tents were shockingly warm. It’s incredible that these two thin layers of fabric could keep us warm and safe in such a hostile environment. I suppose we were helped by the constant sun that heated them up. The only night I was cold was on a foggy day which blocked off the sun. The tent never warmed up and I had to rely on the special -45 sleeping bag, my body heat, and a few hot water bottles that I put in the sleeping bag to stay warm.

As the days progressed a few things became apparent. The entire experience felt like Groundhog Day or The Day After Tomorrow. In many ways the days were identical to each other. It was the same agenda, with the same group of people, in the same setting, with no communications to the outside world. Like in those movies, we improved day after day. It took us less and less time to pack up the camp in the morning and set it up in the evenings. We learnt which clothes to wear and what to eat. To keep my fingers warm I found which liners, when mixed with hand warmers and my mittens worked best. You also must eat every hour to not become hypoglycemic and not lose too much weight. The first few days I struggled as my protein bars and chocolate were so frozen, I could not bite into them. I realized I had to keep my snack for the next stop in my mittens during the walking session. This combined well with soft high calorie gummies and the two Gatorade powder packs I put in my hot water bottle daily. Despite eating 5,000+ calories per day we still lost around a pound per day of body weight. Even the toilet situation became more manageable. Because of the dryness and lack of life, we had to poop in a plastic bag that we carried with us the entire trip. We could also only make 2 pee holes per day and use a pee bottle the rest of the time. Pooping in a plastic bag while literally freezing your ass off is rather unpleasant. Worse, because we are carrying it with us our sled barely got lighter as we progressed. However, as with most things in life we got used to it and improved.

It was interesting to observe that we all struggled in different ways and at different times. The first few days two of the crewmembers suffered from altitude sickness. Some had food poisoning. Many of us struggled to keep our hands warm or goggles not fogged up which made those days painful. Nicholas did not feel hungry one day and did not eat for a few stops which led him to becoming hypoglycemic. He describes that day as the most difficult he ever faced in his entire life. He made it through with sheer grit and willpower, and promptly passed out once we reached camp. I remember finding the windy and foggy days particularly painful. I also felt exhausted for legs 5 through 8 almost every day.

If there was a common theme that emerged from all this is, it’s that we have the ability to push ourselves way beyond what we think our limit is. At some point or another, we all exceeded our physical abilities and dipped into the well of mental fortitude, grit, tenacity, and resilience. Making it to the end of the day was an exercise in mind over matter. It also goes to show how team spirit works as none of us wanted to let the others down by not making it or slowing the group down. We also all supported each other in our times of need.

With infinite relief. We reached the pole on the 7th day of the expedition. It could not have come a day too soon. I am so happy we did not have to do three more days on the ice. I had feared the expedition would be too short. It was perfect. It was long enough to bond with each other, face adversity and rise to the challenge.

We had a blast at the pole. We took infinite pictures both at the geographic south pole and at the mirrored globe that is the representation of the South Pole installed by the countries that have a permanent base there. By comparison, the magnetic south pole moves every year and is thousands of miles away. We enjoyed the heated tents and the delicious food at South Pole station, happy to leave our astronaut food behind us. Even the porta-potties were a welcome relief!

That night turned into a night of drunken debauchery, or at least as bacchanal as one can get when surrounded by a team of men and one woman who have not showered or shaved in 10 days while exercising 8+ hours per day. However, tame it was, it was the perfect way to blow off steam and celebrate our success.

I had originally considered snow kiting from the pole to Hercules station at the coast alone with a guide. That’s 700 miles or 1,130 km and up to two weeks more of expedition depending on the wind. I am beyond happy I did not opt for that option as I was exhausted. Instead, we flew from the pole to Union Glacier station the next day on route back to Punta Arenas the day after.

I took the time to reflect on the trip. I felt so much pride and relief at succeeding, and I wondered if I would have opted to go had I known how difficult it was going to be. Like Kevin, I think ultimately the answer would have been yes given all the learnings, the sense of purpose, and gratitude we felt from the experience. In life we value the things that we fight for and ultimately succeed in getting. This was a perfect example of that.

The overwhelming feeling, I came out of the experience with was one of gratitude. I felt immense gratitude for the disconnection I experienced during these two weeks. It’s extraordinarily rare in this hyper connected world not to have news, WhatsApp, email or any scheduled meetings. While we spoke with our teammates at times, we were alone with our thoughts for extended periods of time making it feel like an active silent Vipassana retreat. I used many of the legs of the trip to sing mantras, meditate, and be present. I used others to daydream and came away with countless ideas.

I felt gratitude to have the ability to have such a unique experience in such a unique landscape. I appreciate how rare it is for people to do this and how special it is. I felt gratitude for the new connections I made. I spent a few hours every day chatting with my team members. Over the course of the expedition, I had meaningful conversations with every one of them and even got to know Kevin and Jack much better than I did before. This was further accentuated by the fact we decided to swap tentmate every night. I also felt boundless gratitude for my teammates and team leaders for the support they gave me when I was struggling.

I felt gratitude for the modern equipment we were using. I read Endurance, the book about Shackelton’s incredible voyage while I was skiing the last degree. I am beyond grateful I was doing this with 2023 gear and not 1915 gear! Coming back to civilization I felt so much gratitude for the little things in life we take for granted but are so magical. Indoor plumbing must be one of the greatest inventions ever, even more so when combined with hot water! Also, it’s mind boggling that we can just go to a restaurant and order delicious food. We are beyond privileged. We just need to take the time to realize it and appreciate it. Perhaps losing the things we take for granted once in a while reminds us of how amazing our lives truly are.

I felt grateful to my colleagues at FJ Labs who picked up the slack while I was away, and to all of you who encourage me and inspire me to go further. I felt the most gratitude to my family and my extended family in the Grindaverse for putting up with me and supporting me on all my crazy adventures. I missed Francois, or “Fafa” as he likes to call himself, enormously, but was so happy to be reunited with him and to tell him all about my adventure. I look forward to going on many adventures with him in the future.

All that to say: thank you!

Such a great story. Your skills as a story teller are getting better. What a great adventure.

Incredibly inspiring – what an adventure! Loved all the details and the digital sabbatical while getting reacquainted with your humanity through nature and suffering!

Having seen some documentaries about residents of Antactica I was assuming that it would have been easier in that you could have simply walked for a bit, then slid on your belly, walked for a bit, slid on your belly, rinse, repeat. But come to think of it. I guess penguins don’t have to pull sleds 😉

I appreciate that you shared such a detailed account of your adventure. Reading the description of your feelings on each leg of the journey and how you dealt with adversity made your story so much more immersive.