FJ Labs’ investment approach stems from its roots (read The Genesis of FJ Labs). FJ Labs is the extension of Jose’s and my angel investing activities. We scaled our activities and processes, but we did not change the strategy.

Most venture capital funds have very well-defined portfolio construction. They invest the funds they raised over a specific period, in a specific type of company, in a specific number of companies, investing a specific investment amount, at a specific stage, in a specific geography. These funds lead rounds and the partners take board seats. They reserve a certain amount of capital for follow-ons and typically do follow-on. Fund rules are such that subsequent funds cannot invest in the companies from the prior fund. The fund does extensive due diligence and invests in less than 7 deals per year.

A typical $175 million dollar VC fund may look like this:

- US only

- Series A focus

- B2B SAAS companies only

- Invests $5-7M Series A lead checks

- Targeting investing in 20 companies over a 3-year period

- 40% of the capital reserved for follow-ons

- Follow-on in most of the portfolio companies

- Partners take board seats

- Investments take 2-4 months from first meeting

FJ Labs does not operate this way. As we did when we were angels, we evaluate all the companies in our pipeline, and we invest in those we like. We decide whether we invest or not based on two 60-minute calls over the course of a week or two. We do not lead, and we do not take board seats. In other words, you could say we invest at any stage, in any geography, in any industry with extremely limited due diligence. Those are the very words that scared away institutional investors and made us think we would never raise a fund.

Given this “strategy,” you might expect that our portfolio composition would vary dramatically over time. In fact, it has been very consistent over the years. There are several reasons for this.

- The number of deals we evaluate weekly has been remarkably consistent over the years

I will detail how FJ Labs gets deal flow in a subsequent blog post. But to give you a sense of scale, we receive over 100 investment opportunities every week. However, we do not evaluate all of those. Many are clearly out of scope: hardware, AI, space tech, biotech, etc. without a marketplace component. Many others are too vague: “I have a great online investment opportunity; do you want to receive a deck?”

If you do not make the effort to realize we focus on online marketplaces and include enough information for us to evaluate whether or not we want to dig further into the deal, we will not reply or follow-up.

On average, we evaluate 40-50 deals every week. In 2019 for instance, we evaluated 2,542 companies which averages out to 49 per week.

2. The percentage of deals we invest in has been largely constant

There is a lot of specificity that goes into “we invest in companies we like.” We have extremely specific evaluation criteria and investment theses that we keep refining. I will detail those in subsequent blog posts. While we invest in every industry, in every geography and at every stage, we do have a specificity: we invest in marketplaces.

Over the years we have been investing in around 3% of the deals we evaluate. In 2019 for instance we made 83 first time investments. In other words, we invested in 3.3% of the 2,542 deals we evaluated.

3. The distribution of deals we receive is not random and consistent over time

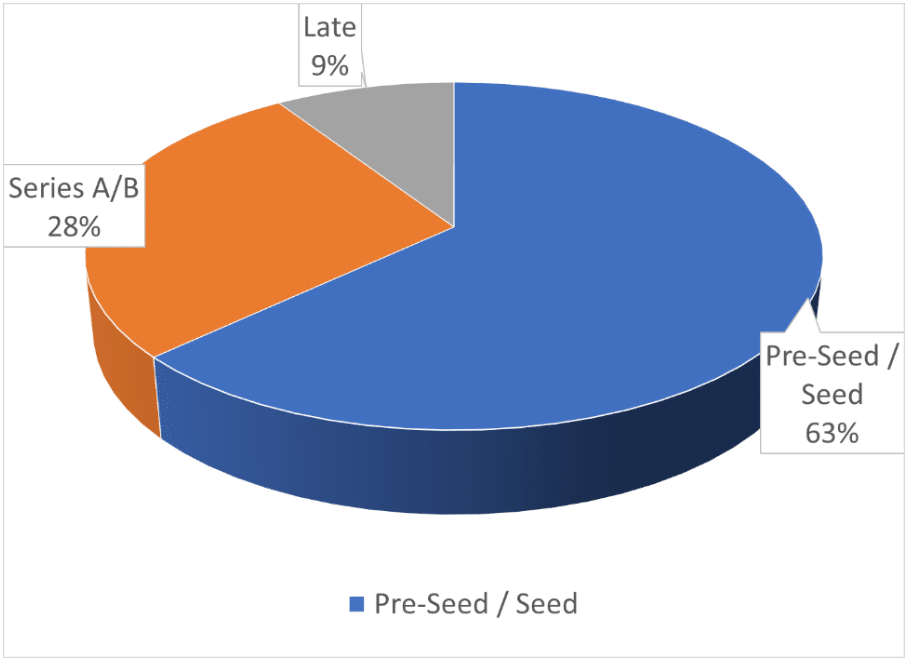

In general, there are many more pre-seed and seed deals than Series A and Series B deals. In turn there are more Series A & B deals than later stage deals. On top of that, because we are known as angel investors who write relatively small checks, we receive disproportionately earlier stage deals that later stage deals. As a result, most of our investments are seed stage or earlier though the number of Series A has been increasing in recent years.

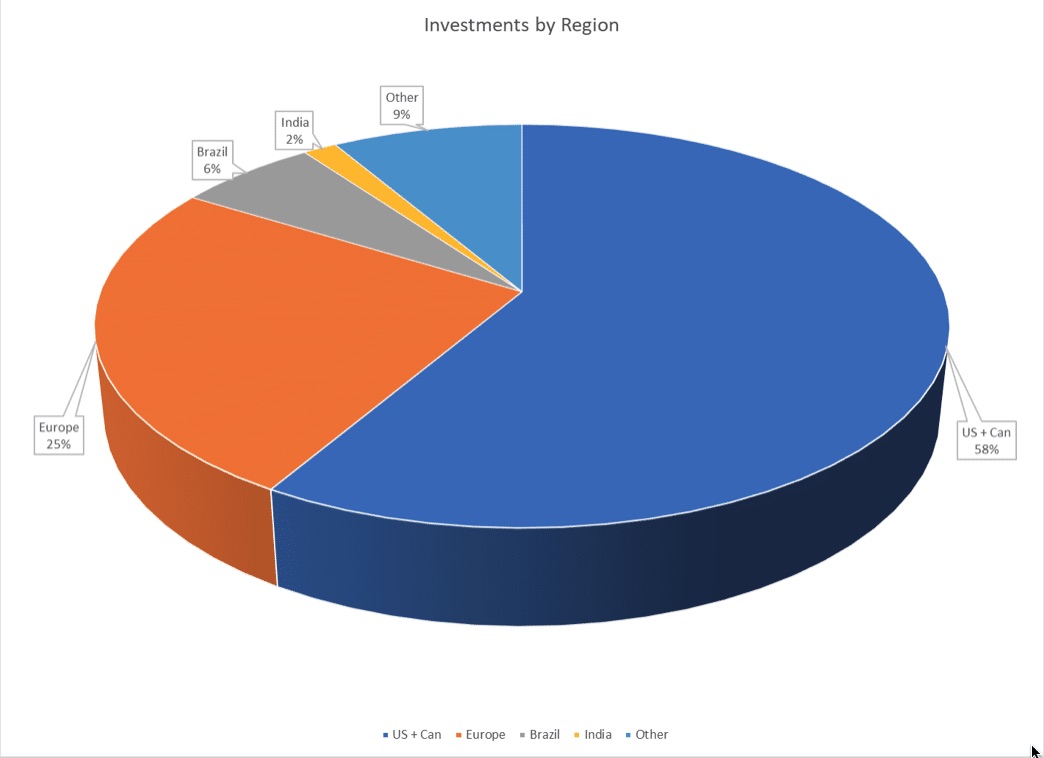

4. While we evaluate deals from any country, we have specific preferences

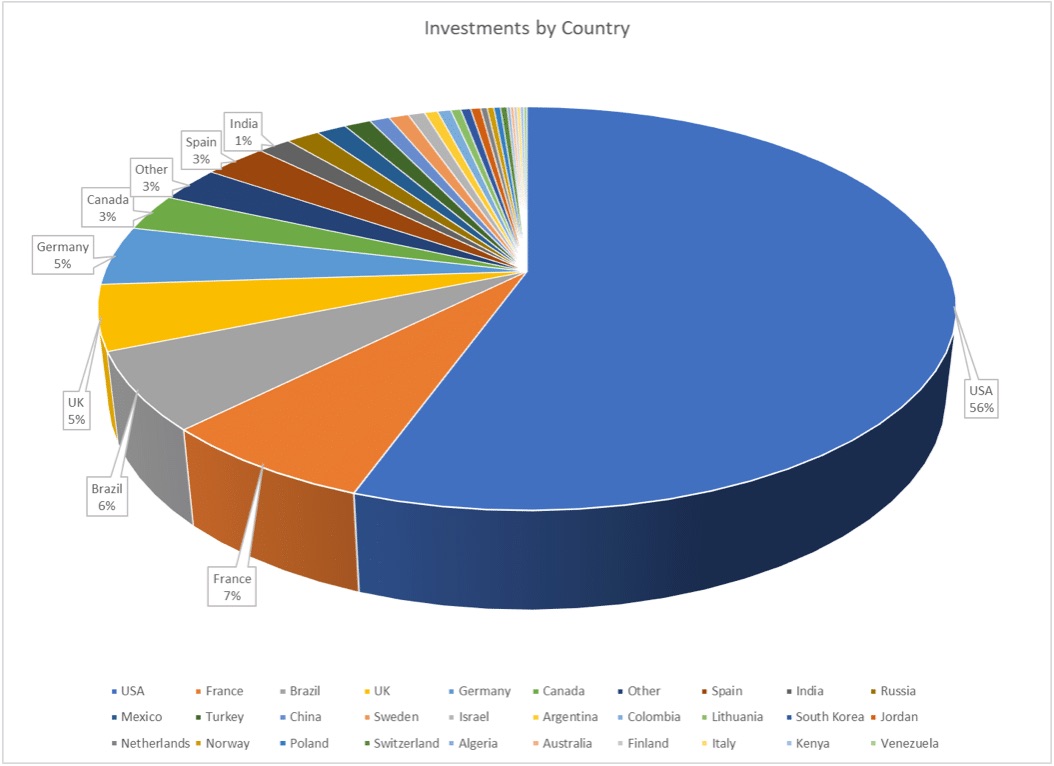

While we are global investors, we are New York based and most of the marketplace innovation is coming out of the US. As a result, most of our deal flow comes from the US and most of our investments are in the US. At the same time, Jose lives in London and I am French, so we get a lot of European deal flow. Given OLX’s global footprint, I am also very visible in many emerging markets.

While we evaluate deals in all countries, when we look at startups in emerging markets, we focus on large markets that have more robust venture ecosystems and financial markets. These days this mostly means Brazil and India. That is not to say we will never invest in smaller markets. We invested in Rappi in Colombia, Yassir in Algeria and Lori Systems in Kenya for instance, but the bar to us investing is a lot higher.

The main issue in smaller emerging markets is the lack of Series A & B capital and the lack of exits. There are rich locals that will angel invest in almost every country in the world. Also if you break out, which typically means over $100 million in revenues and $100 million in valuation, US global funds like Tiger Global will find you to invest (at what would typically be a Series C) wherever you are located.

However, most smaller markets do not have Series A & B investors making it ridiculously hard for companies to get from seed to breakout status, especially if the domestic market is small. Worse there are few exits for those companies, even the successful ones, because the countries they are in are not in the priority list for the large global acquirers.

To date 58% of our investments have been in the US and Canada (mostly the US), 25% in Europe, 6% in Brazil, 2% in India and all other countries combine account for 9%.

Beyond this, we have a few other guiding principles.

A. We focus on marketplaces

My fascination with marketplaces stems from my early fascination with economics. I discovered Adam Smith and David Ricardo in my teens. Their work resonated with me because it explained how the world was structured better than anything else I encountered. This is why I studied economics at Princeton, which further grew my interest in market design and incentive systems.

When I graduated in 1996, I did not think it would lead to anything practical. As a shy, introverted 21-year-old I went to work for McKinsey for two years. Even though I wanted to be an Internet entrepreneur, I felt McKinsey would be the equivalent of business school, except they paid me. Two years later I felt I had learned what I came to learn and was ready to venture into the world of entrepreneurship.

As I started thinking through ideas of companies I could build, I realized many were not appropriate for an inexperienced 23-year-old. Building Amazon-type companies required managing complex supply chains. Etrade type companies required obtaining brokerage or banking licenses. Most ideas were also massively capital intensive. When I ran into the eBay website, it was love at first click. I immediately recognized the extraordinary amount of value that could be created by bringing transparency and liquidity to the previously opaque and fragmented markets for collectibles and used goods that were mostly traded in garage sales offline. I also realized how capital efficient the model would be as it unleashed powerful network effects with ever more buyers bringing every more sellers who in turn bring every more buyers. Moreover, I knew I could build it. Building a site like eBay has its own complexity in terms of solving the chicken and egg problem of figuring out what to start with and how to monetize, but it was the type of complexity that I felt perfectly suited to deal with.

I founded Aucland, a European online auction site, in July 1998. I ended up building it into one of the largest online auction sites in Europe before it merged with a publicly traded competitor, QXL Ricardo. Funnily enough they were much later acquired by Naspers (as OLX would eventually also be). While running Aucland, I was introduced to a group of Harvard and Stanford grads by a McKinsey colleague. I confirmed their belief they should launch an eBay-like site in Latin America and agreed to provide them with the technology and business plan to do so. Deremate was born and became one of the leading auction sites in Latin America until it merged with MercadoLibre prior to its IPO.

I loved building Aucland. I loved the nuance of matching supply and demand on a category by category basis and building a real community of users. After the Internet bubble popped, I built Zingy, a ringtone company, because I wanted to be an entrepreneur and felt I could build a profitable and successful startup in a world with no venture capital. However, it was not true love. It was a means to an end. I made it profitable, grew it to $200M in revenues before selling it for $80M. I could now return to marketplaces.

In the intervening years I had seen both the rise of Craigslist and the first vertical marketplaces like Stubhub and Elance (now Upwork). I was excited to build OLX. It was the company I was meant to build. It’s what Craigslist would be if it was run well: mobile first with fully moderated content, no spam, scam, prostitution, personals and murders, catering to women, who are the primary decision makers in all household purchases. It now serves over 350 million users every month in 30 countries in mostly emerging markets where it is part of the fabric of society. It allows millions of people to make a living and improves daily lives while being free to use.

OLX allowed me to further my craft and further fall in love with the beauty and elegance of marketplaces. As I was busy running OLX with its hundreds of employees around the world, I decided to focus on marketplaces as an angel investor as I felt uniquely positioned to make rapid investment decisions.

This specialization created its own network effect. Becoming well known as a marketplace investor improved my deal flow in marketplaces, improved my pattern recognition and allowed me to develop more robust thesis and heuristics. As FJ Labs evolved from Jose and my angel investing activities, we simply kept going down the marketplace path we were already on.

In 2020, marketplaces remain as relevant as ever. We are still at the beginning of the technology revolution and marketplaces will have a significant role to play in the decade to come and beyond.

B. We decide quickly and transparently

As an entrepreneur I always hated how slow the fundraising process was and how time consuming it was. Weeks go by between meetings with venture capitalists if only because they use time as an element of due diligence. Entrepreneurs must be very thoughtful about running a tight process in order get term sheets at the same time to create the right amount of FOMO. Entrepreneurs rarely know where they stand. VCs who are not interested may just ghost them or be terribly slow rather than outright pass on the investment to preserve the optionality of changing their mind.

It drove me nuts as an entrepreneur and I decided to do the opposite as an angel. I opted for radical transparency and honesty. Because I was so busy running the day to day operations of OLX, I devised a strategy to evaluate startups based on a 1-hour call. On the 1-hour call or meeting I would tell the entrepreneurs if I was investing and why. In 97% of the cases I passed on the opportunity and would tell them what would need to improve to change my mind.

We did not change the process much for FJ Labs, though we refined it in a way that allows us to evaluate more deals and be more scalable. Most startups are first reviewed by a FJ team member who presents their recommendation on our Tuesday investment committee meeting. If warranted Jose or I take a second call after which we make our investment decision. In other words, entrepreneurs get an investment decision after at most 2 calls over 2 weeks. If we choose not to invest, we tell them why and what would need to change for us to change our mind.

If I am on the first call, I still often make the investment decision at the end of the meeting to the shock of the entrepreneur. I find it normal. After all we have clear investment heuristics and strategy and stand by our beliefs. I love clarity of purpose and thought.

C. We do not lead deals

As angels we did not lead deals. When we started FJ Labs it never occurred to us to become traditional venture capitalists and to lead deals. We prefer meeting entrepreneurs, hearing their crazy ideas, and helping them realize those dreams. This allows us to avoid the legal and administrative work that comes from leading deals.

Moreover, as angels we always saw VCs as our friends. We established strong relationships with many of them and started organizing regular calls to share deal flow. Our approach was super successful, and it did not make sense to change it. Leading deals would mean competing with VCs for allocation. There are many amazing deals we would not be able to participate in or be invited to. No one in their right mind would pick us over Sequoia if we were the type of VC that led deals. The beauty is that with current approach entrepreneurs do not need to pick. They can get both the lead VC of their choice and us. Right now, we invest in almost every company we want to, and we love it!

D. We do not take board seats

In a way not taking board seats is the natural consequence of not leading, but we have fundamental reasons for not wanting to sit on boards. Objectively an investor cannot be on more than 10 boards effectively which is not compatible with our highly diversified approach. Worse, I observed that the companies that are failing end up needing way more work and time. In other words, you end up allocating all your time to help the companies going from 1 to 0 and almost none of your time on the companies that are doing the best and are going from 1 to 100. Instead you should be ignoring the companies going from 1 to 0 and spending your time thinking how to create the most value for your rocket ships.

There is also a certain formality and rigidity to board meetings that prevent them from getting to the heart of the matter. Both as an entrepreneur and an investor the most meaningful strategic discussions I ever had were informal 1 on 1 coffee chats rather than formal board meetings. I have been told countless times that the conversation I had with an entrepreneur was the most meaningful they ever had.

Note that not taking board seats does not mean we are merely passive investors. The value we provide takes a different form.

E. Our main value add is to help with fundraising, with offline advertising and to think through marketplace dynamics

Many funds with billions of assets under management have fully fledged platform teams with lots of venture partners. They have headhunters and experts in various areas to help portfolio companies. We do not have the resources to do all those things. Instead we decided to focus on three differentiated ways of helping.

First and foremost, we help startups raise. We either help them complete their existing round or raise future rounds. Ultimately, FJ Labs is not setting the terms of the round. We just want the companies we love to get funded. We do deal flow sharing calls with around 100 VCs every 8 weeks covering almost every stage and geography. We have a tailored approach where we present the right VCs to the right startups. The VCs love it because they get differentiated tailored deal flow. The entrepreneurs love it because they get meetings with top VCs. We love it because the startups we care about get funded.

Prior to the entrepreneur going out to market, we try to do a catch-up call to give them feedback on where they stand and review their deck and pitch. When we feel they are ready, we make the relevant intros.

We can also help think through marketplace dynamics. Should you start with the supply or demand side? How local should you be? Should the rake be 1%, 5%, 15% or 50%? Should the rake be taken on the supply side or the demand side? Should you provide extra services to one side of the market? We see so many marketplaces that we have developed a lot of pattern recognition and can help think through core strategic issues.

Lastly, we can help portfolio companies with their offline advertising, especially TV advertising. William Guillouard, one of our Venture Partners was Chief Marketing Officer at OLX where we spent over $500 million in TV advertising. We developed methods to run TV campaigns the way we run online campaigns with attribution models and LTV to CAC analysis. In several cases, we successfully scaled companies rapidly though TV with better unit economics than through Google and Facebook. Obviously, this only applies to a small subset of portfolio companies which are mass market, have good unit economics and enough scale to justify trying TV, but for those companies it can be game changing.

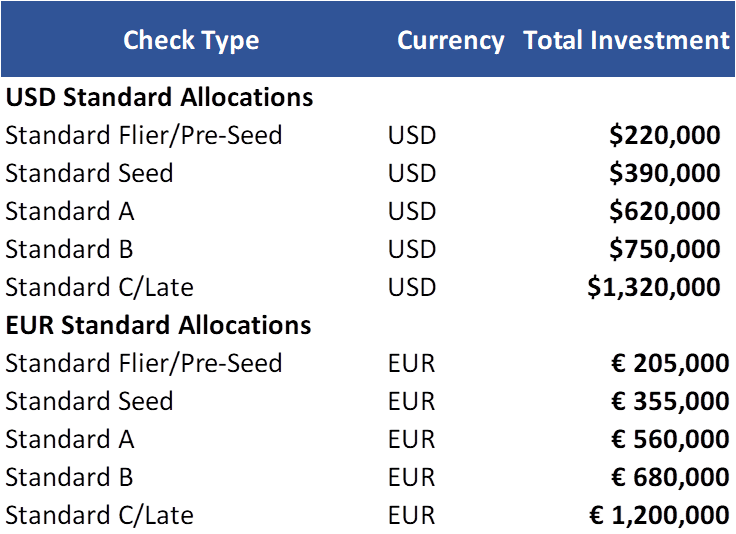

F. We have set check sizes by round

We do not want to be competing for allocation with traditional venture capitalists. We see ourselves as a value-added small co-investor alongside them and we want them to want to invite us to their best deals. This puts maximum check sizes we can deploy at every stage, especially seed stage. In a typical $3M seed round, the lead invests $1.5-2M. To be right-sized relative to the lead, we currently invest $390k at seed. We could probably deploy a bit more capital at each stage and might slightly increase our check sizes in the future if our fund gets a bit larger, but our investment size will always be small relative to that of the lead.

In pre-seed there are often no funds investing. Rounds are often made up of a group of angels. In this case, we may very well be the largest investor with our $220k investment, but we just consider ourselves to be one of the angels rather than a real lead.

We also invest $220 “fliers” in companies we find compelling but are not comfortable investing our standard allocation. We do this for a variety of reasons. Perhaps the valuation is a bit high, the unit economics not quite proven or the startup is in a business we find interesting but do not know much about.

You can find our current standard allocations below.

G. We evaluate follow-ons on a standalone basis

The clear Silicon Valley motto is you double down on your winners regardless of price. We take objection to the second part of that statement. We have always been thoughtful about valuation and it has served us well. As I will detail in a subsequent blog post on FJ Labs’ evaluation criteria if we feel a startup’s valuation is too high relative to traction we do not invest even if we love the entrepreneur and business they are in.

We evaluate follow-ons as though it was the first time we were investing in the business. To keep the evaluation objective, a different team member from the one who made the original investment recommendation does the analysis. The question we try to answer is the following: knowing what we now know about the team and business, would we invest in the company at this valuation?

Depending on how strongly we feel about the answer to that question we try to do super pro-rata, pro-rata or merely pass on the investment. In the last few years, as more funds moved to later stages, we often felt our best companies became overvalued and we did not follow on at those later stages. To date, we followed on in 24% of our investments.

Also, given our fund size, we often cannot afford to do our pro-ratas as they would represent most of the capital deployed. Worse given our small ownership percentage as the companies become later stage, we start losing information rights and no longer have visibility into how well the company is doing. As a result, when we feel the price is right, we sometimes sell 50% of our position in secondary transactions, typically selling to the lead VCs when a round is happening.

In a way we are doing the exact opposite strategy of Silicon Valley: we sell our winners rather than double down on them. This explains why our realized IRR is so high. Part of the reason we seek secondaries is driven by our business model. Contrarily to large funds, we do not live from fees. We just reached our break-even point with FJ Labs. After years of having to subsidize our cost structure with millions of out of pocket investment, the management fees we collect now cover our expenses. However, we still have a way to go. Jose and I are not paying ourselves or reimbursing our expenses.

Our business model is different. We make money from exits. We need the capital from successful exits to keep investing in new startups because we represent such a large percentage of the capital deployed. To date we represent $114 million of the $284 million deployed. We cannot afford to wait a decade for the final exit because we want to continue investing at the rate we have been investing.

As you can imagine such secondary exits are only available in the absolute best companies. No one is interested in buying out positions in companies that are not doing well. Even in the best companies, we can only sell because we own small positions and are not on the board. There is no real signal coming from our willingness to sell other than our need for liquidity. In fact, we are often asked to sell as a favor rather than us seeking to sell. For instance, Andreesen, Greylock and Sequoia may all want to invest in a company at the Series B. The entrepreneur loves all 3 and does not want them to fund a competitor. The funds want at least 15% ownership each. The entrepreneur does not want 45% dilution. They do a primary round for 30% and organize a secondary for the rest. They ask us if we would mind selling part of our position in the secondary as a favor to get the round done.

We thought long and hard about how much we should sell in these situations. In the end we opted for selling 50%. It provides us with liquidity and a great exit, while preserving lots of upside if the company does amazingly well. Our fund multiple would be higher if we held until the end, though our IRR would be lower. However, considering we essentially redeploy all the capital that we obtain from the exit into earlier stage companies where we feel there is more upside, our real multiple and IRR is higher when we pursue the secondary when you consider the return we get from the redeployment of the capital.

H. When the fund runs out of money, we just raise the next fund and follow-ons happen from the next fund

We do not follow traditional portfolio construction. The portfolio is just the sum of the individual investments and follow-on investments we make. The construct is completely bottoms-up. We just deploy the capital we have and when we run out of capital, we raise the next fund. We do modulate the investment sizes to make sure each fund is deployed over 2 to 3 years, but that is the extent of it.

Given that we do not know whether we are going to follow-on, and we only follow-on in 24% of the cases, it does not make sense to reserve capital for follow-ons. Also, many of the follow-ons fall outside the 2 to 3-year capital deployment range of a fund. As a result, we told our LPs we would do follow-ons from whatever fund happens to be investing when we make the follow-on investment decision. We also tell them to invest in every fund to have the exact same exposure we do.

Note that we would not sell the position from one fund to another. There is only one investment decision: we are investing, holding, or selling.

I. If you were successful for us in the past, we will back you in your new startup even if It is not a marketplace

We stick by the founders who do right by us. At this point we backed around 1,400 founders in 600 companies. 200 of them had exits and half of them were successful. Many of the successful founders went on to build new companies. For instance, this is how we ended up investing an Archer (www.flyarcher.com), an electric VTOL aircraft startup. We backed Brett Adcock and Adam Goldstein in their labor marketplace startup Vettery which was sold to Adecco. We were excited to back them in their new startup despite our lack of domain expertise in electric self-flying aircrafts.

In summary, while we do not have a set number of deals, stage or geography we intend to invest in every year, things play out such that we end up having an investment strategy that can be summarized as follows:

- Pre-Seed / Seed / Series A focus

- Set investments sizes per round that average to $400k

- Marketplace focus (70% of the deals)

- Global investors but with most of the deals in the US, followed by Western Europe, Brazil and India respectively

- 100+ investments per year

- Investment decision 1-2 weeks after the first meeting

- We evaluate follow-ons on a standalone basis and follow-on on average in 24% of investments

- We do not reserve funds for follow-ons. We invest from whatever fund we happen to be deploying at the time of the investment

- We do not lead rounds

- We do not join boards

- We help portfolio companies fundraise

To give you a sense of scale, our latest $175M fund will probably have over 500 investments. What is interesting is that while we did not do any modeling or portfolio construction, this highly diversified strategy seems to be by far the most effective. There is a very thoughtful paper by Abe Othman, head of Data Science at AngelList that suggests that at seed the best strategy is to invest in every “credible” deal. It’s born out by Angelist’s performance analysis for LPs that clearly finds that “having investments in more companies tends to generate higher investment returns. On average, median returns per year increase 9.0 basis points and mean returns per year increase 6.9 basis points for each additional company that an LP is exposed to.”

Our returns lead credence to the theory. As of April 30th, 2020, we invested $284 million in 571 startups. We had 193 exits with a 62% realized IRR. I suspect that diversification works well for several reasons:

- Venture returns follow a power law rather than a normal Gaussian distribution curve. It is essential to be in the companies that generate all the returns. Investing in more companies increases the probability that you hit the winners.

- Investing in more companies increases your profile as an investor, which in turn improves your deal flow. This is further strengthened if you establish a brand as the must have investor for a given category as we have in marketplaces.

- Evaluating more companies gives you more data to build pattern recognition to improve your investment criteria and thesis.

The beauty of our strategy is that it is organic and bottom’s up. We evolve it over time as we observe conditions evolving whether they at the macro level, the venture capital industry or in technology specifically. For instance, a decade ago, we used to invest a lot in Turkey and Russia. After Putin invaded Georgia and annexed Crimea, and after Erdogan was elected in Turkey, we stopped investing in both countries as we correctly surmised that venture capital and exits would dry up. Likewise, before February 2018, we did not invest in pre-seed, often pre-launch companies. However, venture capital firms kept increasing their fund sizes. To deploy larger amounts of capital, those funds moved to later stages pushing up valuations at those stages as more capital was chasing the same number of deals. We felt it made sense to be contrarian and to move to earlier stages where capital was drying up. After seeing an increasing number of B2B marketplaces where the marketplace picked the supplier for the demand side, we evolved our marketplace investment thesis.

It is going to be interesting how our strategy is going to evolve in the coming years. For instance, I can imagine a future where we differentiate our early stage strategy from our later stage strategy and create separate funds for those opportunities. Time will tell, all I know is that it is going to be fun!